What is the heaviest element in the universe? Are there infinitely many elements? Where and how could superheavy elements be created naturally?

The heaviest abundant element known to exist is uranium, with 92 protons (the atomic number “Z”). But scientists have succeeded in synthesizing superheavy elements up to oganesson, with a Z of 118. Immediately before it are livermorium, with 116 protons and tennessine, which has 117.

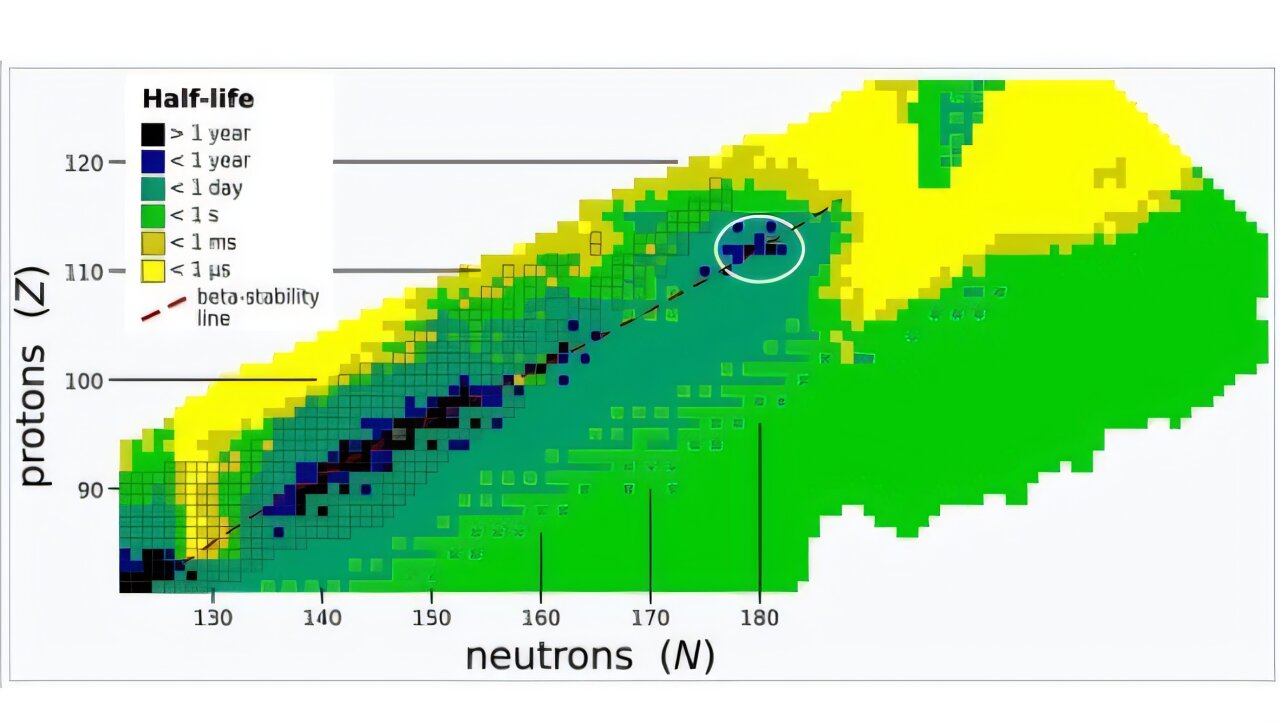

All have short half-lives—the amount of time for half of an assembly of the element’s atoms to decay—usually less than a second and some as short as a microsecond. Creating and detecting such elements is not easy and requires powerful particle accelerators and elaborate measurements.

But the typical way of producing high-Z elements is reaching its limit. In response, a group of scientists from the United States and Europe have come up with a new method to produce superheavy elements beyond the dominant existing technique. Their work, done at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, was published in Physical Review Letters.

“Today, the concept of an ‘island of stability’ remains an intriguing topic, with its exact position and extent on the Segré chart continuing to be a subject of active pursuit both in theoretical and experimental nuclear physics,” J.M. Gates of LBNL and colleagues wrote in their paper.

The island of stability is a region where superheavy elements and their isotopes—nuclei with the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons—may have much longer half-lives than the elements near it. It’s been expected to occur for isotopes near Z=112.

While there have been several techniques to discover superheavy elements and create their isotopes, one of the most fruitful has been to bombard targets from the actinide series of elements with a beam of calcium atoms, specifically an isotope of calcium, 48-calcium (48Ca), that has 20 protons and 28 (48 minus 20) neutrons. The actinide elements have proton numbers from 89 to 103, and 48Ca is special because it has a “magic number” of both protons and neutrons, meaning their numbers completely fill the available energy shells in the nucleus.

Proton and/or neutron numbers being magic means the nucleus is extremely stable; for example, 48Ca has a half-life of about 60 billion billion (6 x 1019) years, far larger than the age of the universe. (By contrast, 49Ca, with just one more neutron, decays by half in about nine minutes.)

These reactions are called “hot-fusion” reactions. Another technique saw beams of isotopes from 50-titanium to 70-zinc accelerated onto targets of lead or bismuth, called “cold-fusion” reactions. Superheavy elements up to oganesson (Z=118) were discovered with these reactions.

But the time needed to produce new superheavy elements, quantified via the cross section of the reaction which measures the probability they occur, was taking longer and longer, sometimes weeks of running time. Being so close to the predicted island of stability, scientists need techniques to go further than oganesson. Targets of einsteinium or fermium, themselves superheavy, cannot be sufficiently produced to make a suitable target.

“A new reaction approach is required,” wrote Gates and his team. And that is what they found.

Theoretical models of the nucleus have successfully predicted the production rates of superheavy elements below oganesson using actinide targets and beams of isotopes heavier than 48-calcium. These models also agree that to produce elements with Z=119 and Z=120, beams of 50-titanium would work best, having the highest cross sections.

But not all necessary parameters have been pinned down by theorists, such as the necessary energy of the beams, and some of the masses needed for the models haven’t been measured by experimentalists. The exact numbers are important because the production rates of the superheavy elements could otherwise vary enormously.

Several experimental efforts to produce atoms with proton numbers from 119 to 122 have already been attempted. All have been unsatisfactory, and the limits they determined for the cross sections have not allowed different theoretical nuclear models to be constrained. Gates and his team investigated the production of isotopes of livermorium (Z=116) by beaming 50-titanium onto targets of 244-Pu (plutonium).

Using the 88-Inch Cyclotron accelerator at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the team produced a beam that averaged 6 trillion titanium ions per second that exited the cyclotron. These impacted the plutonium target, which had a circular area of 12.2 cm, over a 22-day period. Making a slew of measurements, they determined that 290-livermorium had been produced via two different nuclear decay chains.

“This is the first reported production of a SHE [superheavy element] near the predicted island of stability with a beam other than 48-calcium,” they concluded. The reaction cross section, or probability of interaction, did decrease, as was expected with heavier beam isotopes, but “success of this measurement validates that discoveries of new SHE are indeed within experimental reach.”

The discovery represents the first time a collision of non-magic nuclei has shown the potential to create other superheavy atoms and isotopes (both), hopefully paving the way for future discoveries. About 110 isotopes of superheavy elements are known to exist, but another 50 are expected to be out there, waiting to be uncovered by new techniques such as this.

More information:

J. M. Gates et al, Toward the Discovery of New Elements: Production of Livermorium ( Z=116 ) with Ti50, Physical Review Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.172502

© 2024 Science X Network

Citation:

Scientists discover a promising way to create new superheavy elements (2024, October 27)

retrieved 27 October 2024

from YBe

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.