A few years ago, I woke cotton-mouthed and clammy from a dream about a woman I used to know. I had not seen her in person since high school graduation, but once or twice a year, we met in a dream. In this one, we were back in a room with old teachers and friends, where I had to give a talk. I arrived late, half-dressed, unsure what to say. This woman, I’ll call her Alison, sat in front, smirking and perfectly made-up. The tilt of her eyes suggested I was not only dumb, but mean. How had she mastered the art of both villainy and victimhood so well? And how, in real life, did she now see me?

I have long been compelled by a desire for emotional reciprocity. For two people to “be on the same page”, nothing lopsided, the scales balanced. When we cultivate a crush, after all, we want to be their crush too. Suppose it is the same with an enemy? That one’s commitment to, say, having a nemesis might be matched only by one’s desire to be a nemesis in return? As much as I wanted to exorcise Alison from my dreams, the thought of untangling us entirely sent a kick to my side. A little whine of “No”. Part of me was tied to the narrative of our opposition. Like the dark moon on my thigh where I once sat on an old nail, I felt something like affection for what I had survived, for what it said about me: that I was worthy of a nemesis.

Alison and I met on the brink of middle school. The building was new to both of us, but I, who had attended classes on the same campus for years, was asked to show her around. I arrived in a necklace of bead-strung safety pins, tender because my mother had stopped me from buying the shoes I thought I wanted: the same clogs my teachers wore. I, gangly with braces, did not know how to be a teenager. Alison, petite with glossy copper hair, did. She arrived in the right flare jeans and fat plastic flip-flops, filing her nails into almonds and painting them gold so they’d cut the air like machine-smashed pennies. At 12 years old she walked like a starlet who knew her name was in the Oscar envelope.

Our first conversations were full of giddy bonding. We lived nearby, had been placed in the same advanced classes, shared an ambition to edit the student newspaper and were apprehensive about clique politics. I hovered at the sidelines of a friend group I had known for years, and Alison wanted in. One day she asked a handful of us to join her in the bathroom, where, one by one, she doled out tubes of lip gloss. It was such a calculated attempt at conjuring a social group, but, with its blunt pre-teen logic, it worked. I began spending weekday afternoons doing algebra homework at her house. Weekend nights, she hosted big sleepovers in her white-carpeted basement, where her mother stocked all the right snacks. Did we make each other laugh? I can’t recall. When I think of hanging out with her, I feel only the relief of companionship ribbed with skittish unease, an awareness of being constantly measured. Every graded maths test Alison left face-up on the table was a reminder that everything we shared we also competed over.

“Your boob is showing,” she would whisper in class. This was code for “Your necklace has swung around and now the clasp is visible.” She shared this with a conspiratorial smile, as if saving me from social sin. Before I could free my hands from whatever they were doing, she’d have extended a fingernail to my throat and tugged the chain around. “Better,” she’d say, smirking. She was always fiddling with me. Smoothing frizzy flyaways, tugging my shirt if my midriff slipped out, tuning my gaze to transgressions I did not know I’d made. I didn’t enjoy feeling like her project, but I appreciated that, in demanding attention, Alison handed me a script for angsty adolescent days. Her generosity was inexhaustible, I sensed, so long as her feeling of superiority was too. And so I let her put me in gold eyeshadow, introduce me to seltzer and six-minute abs.

A decade later, talking to my sister about why Alison stirred up so much drama, she chalked it up to sex. Alison had it, the rest of us mostly didn’t. It’s not that she literally engaged in it — the opposite, in fact. She vowed to abide by her parents’ rule to avoid solo dates until 16. But she carried herself with the comport of a person with a secret. Unlike many magnetic girls I knew, Alison never tried to be one of the boys. Instead, she sat in their laps. She asked them for hugs, to fasten her bracelets, carry her books, guess her perfume. I, a stubbornly self-contained tomboy, found the damsel performance disheartening. Was this the only way boys would like you? I was too tall to fold myself in anyone’s lap.

Disliking how someone does something — feeling annoyed and, perhaps, threatened, by their movement through the world — is a normal, mundane feeling. I court it when I scroll through bloated destination weddings or when someone breaks the law in traffic. But annoying behaviour does not, in itself, catalyse a nemesis. You cannot get one of those overnight. With a nemesis there is an implication of simmering, slow-cooked antagonism. I am thinking of a chopped onion in a pan. How at the beginning it makes you weep, then, over time, caramelises into something sweet. So too can a good enemy become a kind of beloved. With Alison, my grudge arrived like a stray dog. She made me suspicious at first, but I got used to the feeling. I began to feed it. It was nice, when I felt bad, to have someone to blame. My grudge, which before I hoped would wander on, began to curl at my feet. It kept me warm.

When Mean Girls hit theatres in 2004, Alison and two other girls arrived in matching Juicy Couture and began calling themselves the Plastics. We, their other friends, hated this show of non-ironic popular-girl power. Or is hate the right word?

The dictionary defines a nemesis as “an inescapable agent” of downfall. If punching down is crass and punching up can make you feel like a flea, a nemesis, the fantasy goes, will stare you in the eye. In his book The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin fantasises a history for the now-extinct Dinofelis, a cat with a jaw shaped perfectly for chomping the human head. Could it be, Chatwin muses, that this creature hunted us above other animals? How alluring it would be to read a nemesis into human history! “What is so beguiling . . . is the idea of an intimacy with the Beast,” he writes. “Would we not want to fascinate him as he fascinated us?”

A nemesis is most potent when one believes she has been unduly pursued. At the beginning, Alison and I were not nemeses: we were two young girls clawing for a sense of self. “Female nemeses only exist under patriarchy,” a friend mused recently. I think she is right. Competition between Alison and I was defined not by what passed between us, but the social ecosystem we were in. The world taught us our value was determined by grades and boys; the school showed us there were not enough good ones of each to go around. Just as a fire needs oxygen, a nemesis needs scarcity to survive. It needs to feel as if the person might take something from you — as if their success hinges on your failure. In a small school, we had little to dilute one another’s actions. Gossip did not wash away: it pooled.

Claiming a nemesis holds a strange psychological allure. The soulmate is to love what the nemesis is to loathing — both prop up a mythology of chosen-ness, of special-you. It is impossible to glance at the word “nemesis” without tripping on those two letters in the middle: “me”. We are the ones who animate them. Ours is the blood that warms their limbs, makes them tick.

Alison and I attended school together for seven years and were in the same friend group for at least five of those. But by graduation, we didn’t talk unless we had to. What changed? Alison got broken-up with, then stole a friend’s wallet and tried to frame her ex’s new girlfriend. Alison started spending evenings with another friend’s boyfriend. And then there was me.

I will never forget the night she appeared, unannounced, on my parents’ front porch. It was dark and rainy and mascara had melted on her cheeks. When she told me she needed to talk, I should have known she needed to scream. I was in the early stages of my first real relationship, with an older rock-climber, and Alison had just learnt we were hanging out. “You’ve broken the cardinal rule of friendship,” she said, icy but placid. I knew he had once liked Alison, but I also knew she hadn’t liked him back, that she had just liked him liking her. I hadn’t asked Alison’s “permission” to see him, perhaps because I thought he was fair game or perhaps because I knew she wouldn’t give it.

“But — you don’t like him.” I studied my slippers, trying to avoid her gaze.

“I realised I might like him after all,” she said. “And even so. You should never, ever treat a friend this way.” I felt sick, blamed for something I didn’t deserve, but also something else: an unfamiliar slosh in my gut. Power. For the first time in memory, I had something Alison wanted. I had never seen her so vulnerable, so full of rage.

Had I been terrible? As the girl who was meanest to me in adolescence was, of course, myself, it seemed possible. But it is tiring to loathe oneself. By outsourcing the job to Alison, all I had to do was cultivate my wound. She had made me feel bad for so long, and it was a strange relief to hear our pain was, now, reciprocal. I suppose this was the moment we became real nemeses. When the manic pleasure of our rage outweighed the pleasure of our friendship.

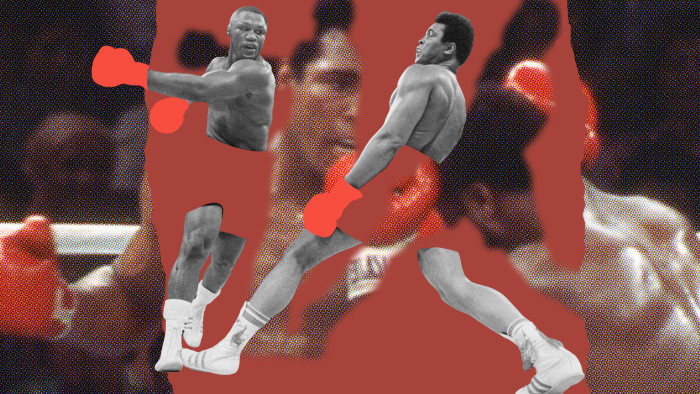

Just as someone with a crush cannot help but sniff for evidence of affection, so a person with a nemesis becomes almost archaeologically fixated on evidence of slight. When, the next day, I told our friend group — about how unfair it was that Alison felt wronged by me, about how my whole family had heard her yell — they were both shocked and unsurprised. By then our feud felt preordained. Not something we had chosen but something that had been constructed for us, a cosmic boxing ring. The Greek goddess Nemesis doled out divine punishment to hubris-struck mortals. Her other name, Adrasteia, means “the inescapable”.

While the other girls and I bonded over a sense of shared Alison manipulation, she began sitting elsewhere at lunch. She got a boyfriend at another school. I felt guilty, sensing my testimony had dealt some final blow, but I also felt relief. I could not tell if it was because a predator had been declawed or a scapegoat had been isolated. Maybe they are the same thing. To think of Alison’s social toppling is to remember how muddy the line can be between the justice seeking of rebel warriors and the blood-hungry boredom of a small-town mob.

One day Alison asked about my dream university, and I told her. At some point, later that fall, I heard she had taken a draft of my application essay from the college counsellor’s trash. What to make of this? She was accepted; I was not. Years later, when I met people who’d attended with her, I mentioned her name, and one of two narratives tumbled out. That she had kicked a woman outside a party; gotten into a screaming match at a basketball game. Then there was the story of her generous leadership, her propulsive career.

In the decade after graduation, bits about Alison’s professional triumphs reached me through mutual acquaintances. Once, when I opened a glossy magazine, she was there, posing in an evening gown. I shut it, quick, as if she might leap out. I had imagined us on different paths after graduation, but a decade later, our careers had strange overlaps. In isolation, her success could make me feel bad about myself, but as long as I thought of us as nemeses, it brought me validation.

Respect of a nemesis is critical. Nietzsche wrote of that “profound understanding” in the value of the enemy, describing a state where “almost every party sees that its interest in self-preservation is best served if its opposite number does not lose its powers”. The more power the enemy has, the more exciting it is when you are caught in crosswind, the way escaping a notable storm brings a greater rush than sidestepping a minor one. It can be flattering, invigorating even, to watch a nemesis excel. Elle Hunt, the author of Why Everyone Needs a Nemesis, shares research that career performance can improve if a person maintains both friends and enemies in a social network. “It can be hard to push yourself in a vacuum,” she writes. Every time I heard about one of Alison’s promotions, I wanted to work harder, to keep up.

The year I turned 30, I stood in a stately Oxford college, watching American high schoolers throw their hands up at an end-of-summer dance. I was their creative writing tutor but also their chaperone, handing out ice cream and talking to students who preferred the company of adults. “I’m so ready to be done,” said the girl beside me. “Once I graduate, I’ll never think of high school again.” I could not help the sound in my throat. A yelp, a laugh. Hadn’t I, at 17, assumed I’d have shaken off nightmares about my former peers, too? A conviction in self-mutability is one of the great palliatives of adolescence. We want to believe we are in control of what we slough. That, around every corner, we might become someone else.

A few months after I left Oxford, Alison appeared in my inbox. We had not spoken in more than 10 years. Her email was blunt. I could not tell if it was anger or if she was just a busy person in a powerful job. She had heard I was publishing a book. Congratulations. Would I be in her city to promote it? The thought of meeting one-on-one made my stomach churn. Would she apologise or would she demand one from me? I hadn’t caused her social alienation, but I had played a part, and I had enjoyed it. By then I knew she was in my dreams not just because of what she had done to me, but what I had done to her. “I will be,” I replied, ever chirpy and non-confrontational. “Would you like to meet up?”

And so, a month later, we sat across from each other and drank pink wine. Our conversation was reserved and relentlessly present-tense. It seemed so obvious, now, that the cadence of our mannerisms was mismatched. In any other context, the differences in our personalities would have kept us polite acquaintances. Our problem, perhaps, had been trying to be too close.

As we spoke, I could not help but tally her life: a high-profile job; a handsome husband; celebrity friends. Our teenage selves would have drooled. My cheeks flushed as I described my own path since high school, moving between cities and boyfriends and gigs, then back to our home town. Watching her nod, though, it struck me that the air between us was flat. The static was gone. I no longer resented her for being someone I couldn’t be. Her life was like a shirt that didn’t flatter my colouring. Nice, just not for me.

All evening I wondered if one of us would bring up the past. Part of me was so curious to know how she narrated it, if she had felt emotional reciprocity, a co-nemesis, with me. Another part of me just wanted the catharsis of this, a future, both of us talking like strangers, chatting about families, relationships, careers. And then we hugged, said we’d keep in touch and turned away. We’ve been in touch a few times since then, but neither of us seems very motivated to keep it up. Stumbling across her name on the internet suddenly evokes very little.

A nemesis compels us to confront what we desire — not in another person, but for ourselves. The older I get, the less I need one. These days I spend less time thinking about what I don’t have and more time feeling grateful for what I do. Alison, ever petite and put-together, with that impeccable work ethic, always made me feel too scattered — in hair, in life, in hand gesture. I am still that way, but I mind it less. I am accepting the limits of myself.

For years I felt as if the only way to find peace with Alison was for a court to lay our case, to hear — from above — whose angst was most justified, who had done more wrong. To sentence us to the right cocktail of shame and apology. But there is no justice for girlhood, for growing into a body that can be both predator and prey. There is just me saying, This was my nemesis, the way I once claimed a patch of forest as a child. Pointing my finger, tiring myself, walking away.

Follow ZGx" data-trackable="link">@FTMag to find out about our latest stories first and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen