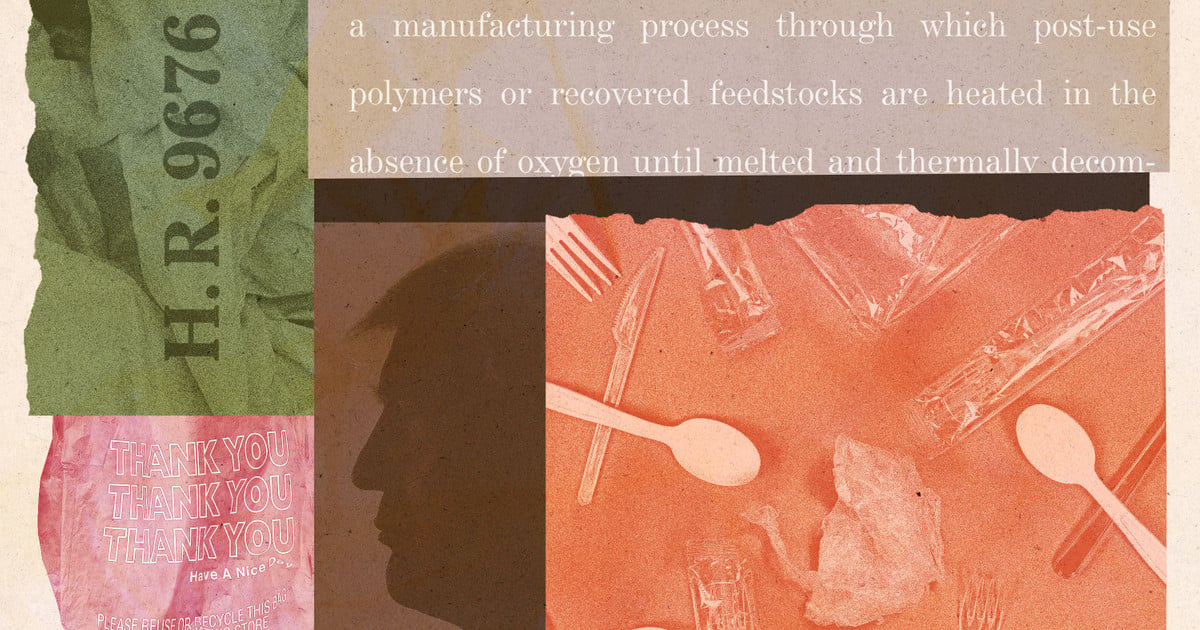

Tucked into a green-sounding federal recycling bill filed last month is a wish list, not of tough new mandates to get a handle on the world’s plastic’s crisis, but of regulatory rollbacks and government assistance that would boost the plastics industry.

Endorsed by petrochemical lobbyists, the legislation is being criticized by environmentalists who are calling it the industry’s own Project 2025 — a playbook for a potential Trump administration to support an oil and gas industry that’s increasingly dependent on manufacturing plastic.

Among the bill’s supporters’ litany of wishes: They want taxpayers to help prop up “advanced” chemical recycling methods that companies have oversold as a solution for plastic-choked oceans and communities.

They want one of the plastic industry’s dirtiest and most inefficient technologies — one akin to incineration — to be redefined as manufacturing, which would make it exempt from air pollution laws.

They want to legitimize an accounting method that allows companies to exaggerate how much recycled plastic is in their products.

And they want to ensure secrecy around how companies process old plastic and prevent states from setting more stringent regulations for the industry.

New here?

We’re ProPublica, a nonprofit, independent newsroom with one job: to hold the powerful to account. Here’s how we’re reporting on democracy this election season:

We’re trying something new. Was it helpful?

Even though the bill itself is a legislative long shot, federal agencies under Donald Trump could adopt some of its most extreme provisions without congressional approval, said Daniel Rosenberg, director of federal toxics policy at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The previous Trump administration had already started the most consequential rollback — the exemption from air pollution regulations — before the Biden administration reversed it.

“The likelihood of really bad stuff happening is exponentially greater under a second Trump administration,” Rosenberg said. The Trump campaign didn’t return a request for comment.

Lobbyists could also break up the bill and try to push it through one piece at a time regardless of who wins the election, he added.

The American Chemistry Council, a prominent plastics lobby, praised the bill as “ground-breaking, solutions-oriented legislation aimed at increasing plastics recycling and preventing plastic from ending up in the environment.” The bill echoes key provisions from a 2022 ACC policy plan. Council spokesperson Andrea Albersheim pushed back on the “inflammatory” characterization that the bill is akin to Project 2025 and noted that it has bipartisan sponsorship.

Rep. Don Davis, a Democrat from North Carolina, and Dr. Larry Bucshon, a Republican congressman from Indiana, co-sponsored the bill, titled Accelerating a Circular Economy for Plastics and Recycling Innovation Act of 2024.

Bucshon is retiring at the end of the legislative session. Davis is in his first term in Congress and faces a competitive reelection race in November; he serves on congressional committees involving agriculture and the military, not science or the environment.

Neither congressman answered ProPublica’s questions about the bill’s creation or its contents. Davis’ press release about the legislation included a statement of support from the CEO of Berry Global, a major plastic packaging manufacturer with a facility in Davis’ district.

Berry supports the act “because it would help modernize the nation’s fragmented recycling infrastructure and significantly increase use of recycled material in new products,” CEO Kevin Kwilinski said in the statement.

Bucshon noted in the release that his district is “home to a number of plastic manufacturers.”

Albersheim, the industry spokesperson, lauded Bucshon’s “long track record of working in a bipartisan fashion on recycling infrastructure legislation.” Bucshon “reached out to a variety of stakeholders,” she said, “including ACC, for perspectives, information and feedback.”

The bill doesn’t include any of the fixes that researchers have found would be most effective in curbing the plastics crisis: capping plastic production, limiting single-use plastic and removing toxic chemicals from plastic products.

The pro-recycling claim hides the bill’s true intent, which is to increase the use of chemical recycling, said Cynthia Palmer, senior analyst for petrochemicals at Moms Clean Air Force. “If you don’t nerd it out and spend your nights and weekends studying these details, then it sounds really good.”

Expanding a Mirage

The plastics industry, which plans to double production over the next few decades, prefers to tackle the plastics crisis through waste management rather than reducing its output. It has long heralded recycling as a cure, despite knowing that traditional methods can barely make a dent in the problem. More recently, the industry has touted new forms of chemical recycling as the solution.

ProPublica explored the most popular form of chemical recycling, pyrolysis; we found it is so inefficient that it yields products with almost no actual recycled content. Companies use a kind of mathematical sleight of hand called mass balance to inflate the recycledness of their most lucrative products by taking credit for the recycled content of other, less lucrative products. It allows a plastic cup with less than 1% recycled plastic to be advertised as 30% recycled.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently issued the first federal policy against mass balance and the California attorney general has sued ExxonMobil for “deceptive” plastic recycling practices, including mass balance. An ExxonMobil spokesperson recently told ProPublica that the company’s chemical recycling process works, and that it has “processed more than 60 million pounds of plastic waste into usable raw materials, keeping it out of landfills.”

The bill would reverse course and require the EPA to authorize various forms of mass balance for recycled plastic packaging. A federal rule along these lines would override state laws and prevent states like California from placing restrictions on mass balance or chemical recycling within their borders, according to the bill.

If an industry-friendly administration takes over, Rosenberg said, the EPA could easily legitimize mass balance. Further changes could come from the Federal Trade Commission, which issues the Green Guides — national guidelines on how companies can advertise environmentally friendly products without deceiving the public. The Biden administration has spent nearly two years working on an updated version of the Green Guides that will likely define what counts as recycling and whether companies can use mass balance to advertise their products.

The nation’s chemical recycling capacity is extremely limited right now. The few American facilities — including one owned by ExxonMobil — can only handle a tiny fraction of the nation’s plastic waste.

The ACC recently told ProPublica that it is lobbying for mandates that would require more recycled plastic in packaging; this would create more demand for the technologies, which would spur growth.

The bill calls for a national standard to increase recycled content in plastic packaging by up to 30% by 2030. To meet that goal, “it will be necessary for the recycling market in the United States to expand its deployment of advanced recycling technologies,” the bill states.

It dedicates a significant chunk of federal resources toward expanding plastic recycling infrastructure and smoothing the way for new chemical recycling facilities. There are few details on the scope and cost of these initiatives, or whether they could work at scale.

Some of the funding would come from fines against companies that don’t comply with the new recycling standard. The bill also requires considerable labor and time from government employees who are tasked with setting up guidelines and requirements to standardize and expand plastic recycling. For instance, regulators must create “data collection procedures” to calculate the annual amount of plastic waste that chemical recyclers could process into new plastic. Another provision points to federal support for using plastic as a construction material, possibly for seawalls that protect communities from sea-level rise and storm surges.

Plastic production was responsible for roughly 5% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 — the very thing driving climate change and severe flooding. The industry’s emissions could double or triple by 2050.

A study authorized by the bill sets the stage for even more government spending. The report, which requires input from plastic and chemical recycling industry representatives, will provide recommendations on financial incentives for improved collection and sorting of recyclables — a necessity for chemical recycling — and potentially expanding the EPA’s National Recycling Strategy to incorporate mass balance. Under a Trump administration, the EPA could update the strategy with that change, Rosenberg said.

93p" srcset="0oK 400w, 93p 800w, R8r 1200w, OYz 1300w, DRc 1450w, XAs 1600w, 3mk 2000w"/>

Credit:

Hannah Beier/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Up in Smoke

During pyrolysis, materials like plastic are heated in a low-oxygen environment until they break down into other chemicals. The process produces hazardous waste and releases carcinogens like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are toxic at very low concentrations.

The EPA has defined pyrolysis facilities as incinerators for decades, and the Clean Air Act defines anything that combusts any solid waste — including discarded plastic — as an incinerator, said Jim Pew, an attorney at the advocacy group Earthjustice.

This bill would count pyrolysis as manufacturing, not incineration. That bureaucratic shuffle would remove federal air pollution regulations that govern the facilities’ toxic air emissions, Pew said. There are no manufacturing regulations that would automatically apply, so the EPA would need to create brand-new rules, among other changes, he added, which is unlikely to occur because it would take sustained efforts over multiple administrations.

“It is not accurate to suggest that the bill would exempt or remove pyrolysis regulation under the Clean Air Act or other environmental laws,” Albersheim, the ACC spokesperson, said. “Instead, the bill aims to address uncertainty under the current laws and correct a misunderstanding about how the technology works.”

When ProPublica asked which federal air pollution laws would apply if pyrolysis is no longer considered incineration, Albersheim said some facilities would not release enough pollutants to meet certain EPA regulation thresholds.

After lobbying from the ACC and others, about half of all U.S. states have passed laws classifying pyrolysis as manufacturing. But the federal government has ultimate authority to enforce the Clean Air Act.

Under then-President Trump, the EPA began the process of redefining pyrolysis as manufacturing. The Biden administration later reversed that decision but “left the door open” for a future attempt, Rosenberg said. If Trump wins, he said, it would be even easier for a Republican administration to remove pyrolysis from the Clean Air Act.

The bill gives regulators authority to audit companies’ recycling practices, but the results could be kept from the public. Any “proprietary information” uncovered during these investigations would not be subject to the Freedom of Information Act. Journalists and researchers routinely use FOIA to access government records and inform the public about corporate wrongdoing or public health threats.

Trade secrets are already protected under FOIA; Rosenberg fears the wording of the bill could broaden the definition of what’s exempt from public disclosure. The bill’s co-sponsors didn’t respond to questions seeking clarification.

Palmer of Moms Clean Air Force said the bill gives the industry cover as it tries to triple plastic production over the next few decades. All these efforts to increase recycling through whatever means possible are meant to “divert our attention” from the “sinister” effects that plastic has on the environment and our communities, she said.