Jon Wiener: From The Nation magazine, this is Start Making Sense. I’m Jon Wiener. Later in the hour: Trump supporters in Appalachia: Arlie Hochschild has spent years talking with them about how they understand their lives. Her new book is “Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right.” But first: Why It Will Be Harder for Trump to Challenge This Year’s Election. Rick Hassen will explain – in a minute.

[BREAK]

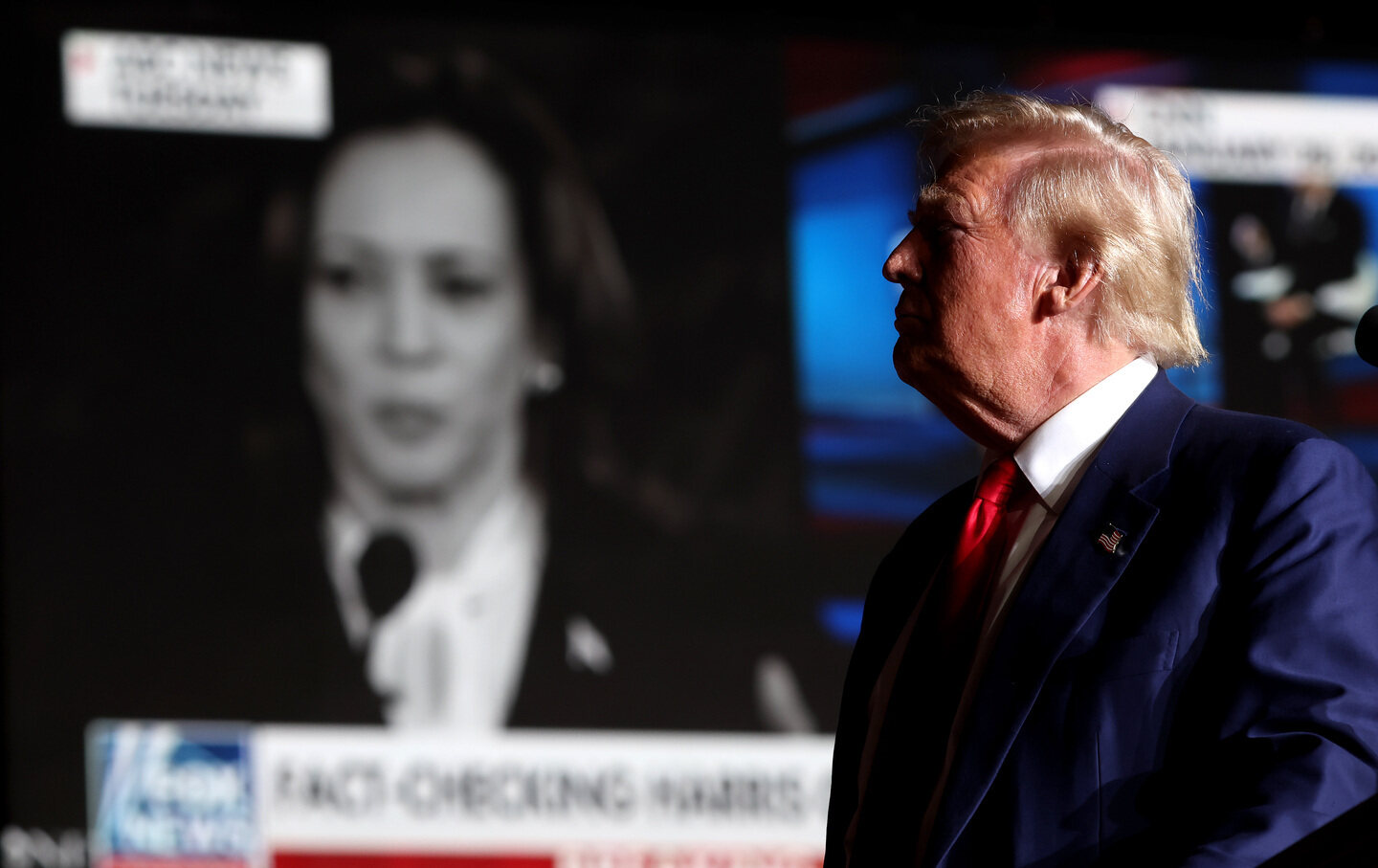

Trump has made it clear he won’t accept the results of the 2024 election if he loses, and Republicans are doing everything they can to reduce the number of Democratic voters and make it harder to vote. Of course, we haven’t forgotten the possibility of another attack on the Capitol to prevent Congress from declaring the winner of the Electoral College next January 6th.

But it will be harder for Trump to challenge this year’s election, that’s what Rick Hasen says. He’s one of our leading authorities on voting and elections, professor of law and political science at UCLA, where he directs the Safeguarding Democracy Project. He’s written many books including Election Meltdown: Dirty Tricks, Distrust, and the Threat to American Democracy, and his writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Slate and The New York Times. Rick Hasen, welcome back.

Rick Hasen: It’s great to be back with you.

JW: Let’s start at the end, Congress meeting next January 6th to count the electoral votes. The Department of Homeland Security has designated January 6th, 2025, as a National Security Special Event, giving it the same level of security as presidential inaugurations and political conventions. So, how will that work?

RH: Well, I think they’re just being prudent. Even if Donald Trump were not running for office and even if the rhetoric were not as heated and we didn’t have assassination attempts, I still think it’s prudent to be just like we would protect any presidential inauguration, to protect this process, which is really the formal means by which we designate who the president is and start that peaceful transition of power.

JW: This means protest demonstrations won’t be able to get within several blocks of the event, that there’ll be other police departments standing by, potentially the National Guard. Let’s not forget Trump was still president last time. He didn’t call the National Guard; he didn’t mobilize other federal forces to help defend the Capitol. That’s certainly not going to happen next January 6th. Also, a lot of the most militant and violent people from 2021 are now in prison serving long sentences. So I don’t think there’s going to be a repeat of the attack on the Capitol.

RH: You never know. The government should be prepared, and they should be prepared in 2029, 2033, et cetera.

JW: What about the electoral vote count itself? Last time we had of course the fake electors scheme, we had some states threatening to send competing slates of electors pledged to opposing candidates. There are efforts now underway in some of the red states starting with Georgia to delay the reporting of election results by claiming extensive voter fraud that has to be investigated.

The plan there, we are told, would be to prevent any candidate from getting the 270 electoral votes required to win, which could throw the election to the House of Representatives, where, according to the Constitution, the 12th Amendment, which only now we’re studying closely, says that each state’s House delegation would cast a single vote if the House of Representatives fails to count the electoral votes, and this overriding of the Electoral College would probably favor Trump. So, what about these Republican strategies to undermine the Electoral College and throw the election to the House?

RH: I think the first thing to recognize is that the way in which Donald Trump tried to subvert the election in 2020 would be harder to accomplish in 2024 — for two reasons. First, at the end of 2022, Congress passed a law called the Electoral Count Reform Act, and it clarified a bunch of things — like the vice president can’t simply throw out the votes. Of course, Kamala Harris is the vice president, so she’s not going to be doing Trump’s bidding, but this is a good change to make for the future.

It also talks about what the standard is for objections, it also talks about what happens if a governor or state’s governor doesn’t act to sign the certificate that goes to Congress. It also talks about whether states can step in and appoint alternative slates of electors — and they generally cannot. So, that’s one change that has made that attempt harder.

The other change is that the United States Supreme Court decided a case in 2023 called Moore v. Harper. It’s a complicated case, but the part of the case that matters here is that that the court rejected this extreme version of what’s come to be known as the independent state legislature theory, which says the state legislatures would have some free-floating power to basically do whatever they want and ignore state constitutions, state courts, the governor and everything else, and the court said that’s not how any of this works. So, both of those things would make it harder.

JW: A lot of people are worried about Georgia failing to report on time the results of their vote in an effort to throw it to the House. What would happen now under the new Electoral Count Act?

RH: The first thing is that if there’s a delay in Georgia, because some local boards are dragging their feet as they’re doing purported investigations, and that’s possible that that’s going to happen thanks to what this very Trumpy election board has put in place. Well, first of all, the governor and the Secretary of State who stood up to Trump last time, both Republicans, they would likely not stand for it. You could go to state court and get orders to get these people to do their jobs. We’ve seen that happen in other places around the country when there’s been delayed certification in 2022, for example, in New Mexico.

Federal courts can step in, because the Electoral Count Reform Act has a provision for federal court to step in. Also, just what you would be doing essentially if you denied the Electoral College votes of Georgia to be sent in, if you’re able to stop them from being sent in, you’d be disenfranchising all the people of Georgia from participating in the presidential election. That’s a pretty serious violation of voting rights, so the federal courts could step in, and I think that there are enough guardrails to push back on this.

JW: Let’s say that we have the worst-case scenario, the governor of Georgia does not report the votes of Georgia in an effort to prevent the majority of 270 being reached by Kamala Harris. What happens then? Does it go to the House?

RH: Well, first of all, there’s a particular provision in the Electoral Count Reform Act to force the governor to do the right thing, to go to federal court and get the governor to do it. But you have a bit of a misunderstanding of the requirement of 270. There is no requirement of 270. There is a requirement of the majority of the Electoral College votes cast. If Georgia doesn’t send anyone, that changes the denominator. So, you have to subtract out Georgia’s Electoral College votes and now you have something less than 270.

It still could affect the outcome if the election is otherwise very close and if the math works exactly, but it’s just harder to do. But that doesn’t trigger a contingent election because that doesn’t automatically mean no one gets a majority. So, the 12th Amendment contingent election only happens if no one gets a majority from the denominator. You take the denominator, divide it by two, someone has to get half plus one. If no one does, that’s typically the case that would happen if there were say three viable candidates getting electoral vote. So, this is not very likely to happen.

JW: Right.

RH: There are other things that could happen that make me worried.

JW: What are your other worries about January 6th?

RH: Here’s my biggest worry about January 6th. Suppose that Harris squeaks by, wins Georgia, that puts her over the top, and Trump is yelling ‘fraud,’ and we get to the House and let’s say that Republicans control the House. They just ignore the votes and say, ‘Well, we think there’s fraud in Georgia. We object, we’re not counting those votes. So we’re going to throw those out,’ and let’s say it’s close enough that that actually makes a difference, ‘that we’re going to award those votes to Trump.’

JW: You’re talking about counting the electoral votes on January 6, when the new rule is that it takes 20 per cent of the votes to object to a state’s report of its results. If 20 percent object to Georgia’s vote for Kamala, claiming there’s fraud, then the Senate and the House meet separately to vote on the merits of the objection. And If Republicans control both the Senate and the House, they could award Georgia’s electoral votes to Trump – even though Kamala won Georgia. What happens then?

RH: The Democrats are upset and go to the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court says, ‘Sorry, this is a political question, we’re not getting involved.’ That worries me more.

Now, could they do that? Well, I would say not legally, but now we’ve left the realm of election law and we’ve gotten into I think what would really fairly be called a coup, not as a metaphor, but as an actual statement of trying to overturn the results of a Democratic election.

JW: If the Democrats regain control of the House, doesn’t the new House take office before January 6th?

RH: That’s right. So the new House will take office on January 3rd, and so my concern here would be about what the new House would do if controlled by Republicans. There are of course Republicans who are worried that Democrats take control of the House, and that they say, ‘Well, Trump is disqualified from serving, we can’t count the votes for him.’ They run to the Supreme Court. Does the Supreme Court say, we’re not getting involved? I’m guessing the Supreme Court gets involved there. So we’ll see.

JW: Moving back in time: election day, Tuesday, November 5th, what do you think are the chances we will actually know the results of the election that night or the next day?

RH: Well, the very first thing to say is that it depends on how close it is. If Pennsylvania is necessary to answer the question, then I would say there’s not a great chance we’ll know who the winner is by the morning after the election. That’s because Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, unlike most other states that have large numbers of mail-in ballots coming in, do not allow the pre-canvassing or processing of absentee ballots.

This is something that is done in lots of Republican states like Florida, right? So this is not something that is a democratic issue, but Republicans in the state legislature have blocked this change. Even though we know that this period between the time that the votes are done being cast and the time that the winner is unofficially determined is a very dangerous period.

You may remember Donald Trump after the election, 2:00 in the morning: “Frankly, I did win this election.” That was when he made that statement. It’s a very dangerous period, it’s very worrisome and it’s completely avoidable. Florida almost always can tell you the winner of the election by the time you go to sleep if you stay up late enough on the night of election day. So it doesn’t have to be this way, but if the election is close, we will not know. Just to remind you, in 2020 it was not until the Saturday after election day that we knew who had won. Now, there will be less voting by mail in Pennsylvania this time than in 2020.

JW: Why is that?

RH: The reason we had so much voting by mail was because we were in the middle of a pandemic, and there were a ton of people who were voting by mail, because they didn’t feel safe or comfortable going to a polling place in person. So already we’re seeing in places where they don’t do mostly all mail elections like Utah or Colorado, or places where it’s very prevalent like California, I don’t think we’re going to see a lot of drop off there, but in places like Pennsylvania where they didn’t have a big history of it, I think many people likely revert to voting in person.

JW: Last time, in 2020, that period just after election day was filled with Trump’s lawsuits trying to get courts to throw out the election results in blue states, and Trump’s lawyers are no doubt already drafting lawsuits to do a better job this November than they did last time, when they lost 60 out of 61 cases or something like that. The most notable of those cases was Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s suit to throw out the Electoral College votes of four other states. What do you think are the chances that Trump’s lawyers will have more success this year?

RH: I think the chances are lower. And they were not successful last time. Remember, when we had the pandemic, lots of states were changing election rules, more voting by mail, changing the dates of primaries. These changes spurred lawsuits, arguing that the changes were not allowed. Also, places that failed to make changes spurred lawsuits, and then some courts made changes which were then reversed by other courts. We don’t have that dynamic going on now.

I have to say, for the most part, I’ve been underwhelmed by the pre-election litigation this time. Not the amount of it, there’s plenty of it, but by the seriousness and the scope of it. In order to come up with a plausible theory, you have to have something you can point to, point to fraud. You may remember Rudy Giuliani famously saying in one of the Pennsylvania cases, “Oh, we’re not alleging fraud.” Even though he had been alleging fraud. Once you’re in court, you actually have to prove it.

So unless there’s some major fraud or some major snafu with how the election is run, then what are you going to point to? Really the way that you get an election result overturned, think back to the year 2000, Bush versus Gore. That was a case where millions of ballots were cast, but it was within 2,000 votes. By the end, it was within 500 votes. It has to be razor-thin, and then sure, then you can start dissecting things and ask ‘why’d they count this ballot? This marking only filled out half an oval,’ and you can start fighting over the intricacies of that.

Because just like anything else that humans do, nothing is done with perfection. People do the best they can, and if you have to figure out who has won an election to the person, because it’s within a very, very small number of votes, then it’s possible to litigate your way to victory. But we’re talking about a very small difference between the candidates. Beyond that, something’s going to have to go very wrong with how the election is run for there to be some viable theory to change the election results.

JW: A couple of news stories just in the last couple of days have raised new alarms. The New York Times recently reported on how it’s going in states that have new laws that allow private citizens to file mass challenges against other people’s eligibility to vote. There’s a big story over the weekend about how in Georgia one woman has legally challenged more than 1,000 voters in her county.

This is because Georgia’s Republican legislature passed what they call an election integrity law that permits any registered voter to file an unlimited number of challenges. That law requires election clerks to schedule hearings and send up to four letters to each voter who’s been challenged, which means the registrar’s voter is hopelessly overwhelmed by the requirements here.

We’re told that in Pittsburgh one Trump supporter has challenged more than 25,000 registered voters based mostly on change of address data. There’s an election monitoring organization called True the Vote with big Republican money behind it that has filed more than 640,000 challenges in 1,322 counties, and in these places election officials have been overwhelmed. Most of these challenges apparently are not just to Democrats, but to Black voters. What did you think of those reports? How serious do we need to take them?

RH: I think that there’s a great potential to harass election officials, to harass voters as well, to muck up the works. I don’t think it’s going to lead to large scale disenfranchisement. I think people are very aware of these challenges and there are lots of lawyers. I get contacted by lawyers almost every day, asking “Where can I volunteer?” Because people, they’re aware that there are these shenanigans going on, and most of this is based upon very flimsy evidence of someone’s lack of eligibility.

It’s really about harassment, it’s about delegitimizing democratic victories. It’s a political strategy. It’s not a legal strategy that is likely to bear a lot of fruit. But they’re grifters. They’re people who are just trying to make a buck by claiming that they’re fighting fraud, and it’s despicable conduct.

JW: The New York Times last weekend published an astounding expose of just how far Chief Justice John Roberts has gone to protect Trump recently. They reported on the basis of internal documents. I’m sure there’s great alarm at the court about how these got into the hands of Adam Liptak. Roberts personally engineered the ruling granting Trump immunity from criminal prosecution and pushing off any trial for his role on January 6th until well after the election.

This was an epic win for Trump. And of course there are many ways that elections end up at the Supreme Court. I wonder what you made of that reporting about Justice Roberts and the possible role of the court if, I don’t know, the Electoral Count Reform Act somehow gets to the court?

RH: So, the first thing to say is that it’s remarkable that these documents did get out. Jodi Kantor and Adam Liptak wrote what is certainly the biggest inside scoop at the court since the release of the Dobbs draft opinion before that one came out, the abortion case, in 2022. It says something about the court that this dirty laundry is getting aired in public. It says something about some dynamics at the court, and we can only speculate as to who’s doing what here, but it to me marks a major change in John Roberts’ view of the role of the court.

I had written a piece at Slate back when both the Trump disqualification case out of Colorado and the Trump immunity case were both coming before the court, and I predicted some kind of grand bargain, that John Roberts behind the scenes would be looking for a way to compromise, come up with two opinions that were unanimous or nearly unanimous, find a way for the court to speak in one voice. Kind of like when Richard Nixon’s cases got before the Supreme Court in the 1970s.

JW: Yeah, you were very convincing. You had all of us thinking that.

RH: I couldn’t have been more wrong. And where did I go wrong? It’s that I thought the John Roberts of today was like the John Roberts of yesterday. He clearly was motivated, not by a concern that animates me every day, which is are we going to see our next election subverted? But instead, what’s it going to mean to some future president if someday down the line the president wants to act and is worried that if she eventually leaves office, she could be subject to some kind of criminal prosecution from a rogue Department of Justice later on down the line. Let’s not focus on the fire that’s raging right in front of us, let’s worry there might be a fire in 20 years that could create a problem. Let’s store our water and hold it for the fire in 20 years rather than douse what we actually see.

There wasn’t a word in that Trump immunity opinion or in the Trump disqualification case condemning the attempt to mess with the peaceful transition of power or even celebrating our democracy. To me, sometimes it’s just as important what the Supreme Court doesn’t say as what it says. Here the court didn’t say anything bad about that. It was really bad about, ‘oh, these prosecutors are going after these poor presidents.’

I mean, so what does this say? Does it say that the Supreme Court is in the tank for Trump? I hope it doesn’t say that. I think what it does say is that John Roberts and the conserves in the court have a very different worldview. They’re much more willing to accept the idea that Donald Trump might be a victim of selective prosecution. I mean, I think that the New York prosecution was a mistake. That’s a topic for another day.

I don’t think that was well-founded to turn that into a felony, I think that was politically motivated, but whatever those things are, how would that affect, say, how to read the Electoral Count Reform Act? All I can say is if you go back to Bush versus Gore, all the liberals on the court ended up siding with the Democrat, all the conservatives ended up siding with the Republican. When the stakes are this high, you really hope that the judges can rise above politics, but you can’t expect it.

JW: Bottom line, what do you consider the greatest vulnerability in this election? What’s your biggest worry?

RH: My biggest worry is that we have a very close election, that there will be attempts to try to subvert the outcome of that election potentially through violence. Spoiler alert. If you remember in Succession, near the end of that show there was the burning of 100,000 ballots that were stored that hadn’t been counted yet coming out of Milwaukee. That kind of thing is possible, and that worries me, that someone will actually try to interfere with the tabulation and reporting and confirmation of our election results in 2024.

JW: Rick Hasen – he wrote about why it will be harder for Trump to challenge this year’s election for The Wall Street Journal, and you can read his election law blog online at electionlawblog.org. Rick, thanks for all your work, and thanks for talking with us today.

RH: Thank you. Take care.

[BREAK]

Jon Wiener: Bill Clinton at the Democratic National Convention had some advice about talking to Trump supporters. “I urge you to meet people where they are,” he said. “I urge you not to demean them. Treat them with respect just the way you’d like them to treat you.”

Arlie Hochschild has been doing that with Trump supporters for a while now. She taught sociology at Berkeley for many years. She’s written, I think it’s nine books. Her last one, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning On the American Right, was a New York Times bestseller and a finalist for the National Book Award. We talked about it here. Her new book is Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right. Arlie Hochschild, welcome back.

Arlie Hochschild: Thank you very much, Jon.

JW: To try to understand Trump supporters, over the last seven years, you talked to dozens of white men in one of the poorest and one of the whitest places in the United States, Pikeville, Kentucky. It’s also one of the places in the country where Trump’s support has been highest. 80% of Pike County voted for Trump in 2020. Tell us about Pikeville and about Kentucky’s fifth Congressional District.

AH: You’re right, it is the second poorest and the whitest congressional district in the country, and it’s remarkable in other ways. It has a high proportion of people who are out of the labor force. Only 56% are actually working or have jobs. That doesn’t mean that they don’t work. A lot is off the grid. A lot of injured coal miners are on disability.

JW: We should say this was coal country.

AH: It was coal country. But coal is out, opiate crisis is in, and people don’t feel the government has seen or recognized the dilemma that they face. It’s depopulating. People leave for the Midwestern cities, industrial cities, for work. They may find work there or not. Come back. It’s a local story that I think tells a national story about non-BA whites that make up 42% of the American population. And that group has gone from left to right. They’ve given up on answers from the left, are turning right, and I went there to find out how life looks to them, and would there be a way to reach them with better answers than the ones they’re faced with this next election?

JW: J.D. Vance in 2016 before he became a Trumper, described Trump’s emotional appeal in places like Pikeville as cultural heroin. He said that Trump “makes some people feel better for a bit, but he cannot fix what ails them and one day they’ll realize it.” You are interested in how Trump makes some people feel better for a bit. How do you understand that?

AH: Well, I feel like this is an area of the country and it’s a sector of the population who have felt shamed, and I feel we need to look at that. Shame and pride are a language of their own to which politicians speak, and we need to be bilingual. I feel like we’re looking for policies, we’re looking for rational answers, we’re scratching our heads if Trump seems to digress, but actually he’s speaking a different language that we are not understanding. And I think it’s urgent that we begin to read the world in a way that 78 million people who in 2020 voted for Trump, the way they read it. It feels very urgent to me and that’s what the book’s about. I think Trump speaks to that shame. I think he’s a shamed person. He knows about shame. He’s very averse to it. He will not be shamed, is especially sensitive about it.

And he’s tuned into a whole sector of the population because they have been divested from. They are the losers of globalization, these red states. And because they fall into what I call a pride paradox. They have a very individual-centered view of pride and shame, so that if they succeed, they take personal pride and success. If they fail, they take personal blame and shame for that failure, even though the failure is caused by the loss of a sector, automation, offshoring. Whereas people in the blue states, they’re living in a luckier sector of the American economy, stronger industries, more urban, and they’re more contextual in their idea of taking credit and blame. So if they succeed, well, yes, but a lot was going for me. Or if they fail, yeah, a lot else in my context accounted for that failure, so they’re less sensitive.

So what we have are a group of people in a declining economy, and whites without BAs, relative to either whites with BAs or Blacks with or without BAs, they’ve been sinking in the last two decades. So that whole sector has taken a hit and it’s doing so with more old-fashioned individual-oriented notion of pride. So they’re a shamed sector and vulnerable to appeals to that shame. And I think that Trump has a shame shielding ritual that he puts us through, and it’s got four moments to it. In moment one, he says something provocative like ‘all immigrants are rapists or criminals.’ Then there’s moment two where the punditry shames him. ‘You can’t say that. Look, you’re an American president. How can you possibly? We’re an immigrant society.’ So moment two, the punditry shames him for his provocation. Moment three, he becomes the victim of the punditry’s shaming. Look what they’re doing to me. This hurts. This is awful. I’m a victim like you have been a victim. I’m a victim.’ That’s moment three.

JW: And these people are the elites from the West Coast and the East Coast who are privileged and control everything.

AH: Exactly, exactly. And you are being shamed by them in this ritual. And then moment four is the big deal. It’s the cathartic moment where Trump rails against the shamers. Now, the thing is that liberals and Democrats are looking at moment one and two. He said something terrible. He got shamed, and they end with the judgment. There’s no curiosity beyond the judgment. Then three and four is what Republicans and the conservatives are looking at. He’s so shamed and he’s getting revenge for himself and them. And so I think this ritual that each moment changes shape depending on the week’s news, but there is a logic to it and we’ve got a charismatic figure here who’s working through his powers, through his relationship to his constituency. They’ve given up on bureaucratic leadership and the government, so one big man will fix all, and this is his mantra.

So we need to, I think first of all, get curious about what goes on for actually the whole 78 million people who voted for Donald Trump and especially for this embattled sector. And we need to reach out. We need to try and understand and talk to them in ways that they can hear.

JW: Matt Bai wrote recently, “If we’re talking about treating Trump voters with basic respect, I’m all in, but empathizing with them, after all we’ve seen, I’m afraid for me, that moment has passed. It’s one thing to say in 2016 that disillusioned voters couldn’t be blamed for taking a flyer on a TV celebrity over a politician they didn’t trust. I get that. Maybe it even made sense four years later to say that Trump’s Legions still believed he was trying to protect them from immigrants and from China. But now, after the violent sacking of the Capitol, after Trump’s promise to behave like a dictator on day one, after eight years of bigotry and baseness and flat-out lies, if they are ignorant, then their ignorance at this point is willful.”

Now, actually, you don’t think they are ignorant about Trump. They understand that Trump is, in your words, a bully. But what?

AH: ‘He’s a bully, but he’s our bully.’ They don’t respect him as a Christian particularly, and they will say right off that he’s self-centered and he is a bully, a bully to defend them, and they are otherwise without defenders.

JW: But what about the January 6th attack on the Capitol? Did any of your white men from Pikeville participate? And what did people tell you about January 6th afterwards?

AH: No, they didn’t. But I did look at all the testimony of people in Kentucky who were convicted, and I talked to them a lot about it. Some said, “I didn’t go, but I wish I had.” Some said, “Oh, January 6th, that must have been Antifa dressing up as people like us.” At first, they didn’t believe it. Then one man actually said, “Well, you know that platform where there was a noose hanging?” As in hang Mike Pence. He said, “Well, yes, there was that platform, but it was just as small as the telephone booth you see out the window.” So they were in denial. But I think left liberals are in denial too if they think that simply judging people for voting for a dangerous man is enough. It’s not enough judgment just to say, ‘Look, they’re wrong. They’re deluded. They must be crazy.’ I hear this actually a lot and I’ve had actually a sociologist friend, even a psychologist to say, “Oh, I don’t know how you talk to these people. They’re wrong. They’re deluded. They must be stupid.”

I think I want to stop people right there and say, ‘Actually, who’s in denial? If you think that your simple judgment of 78 million followers is enough to stop them, you’re wrong actually. You’re denying something.’ And there’s a lot of research comparing liberals with conservatives on their openness to deal with people that don’t agree with them. One Pew study, I think it was 2021, compared liberal Democrats with conservative Republicans and asked, “Look, do you ever cut off conversation when you find that somebody says something that you disagree with?” Liberal Democrats were something like three times more likely to cut off connection than were conservative Republicans.

And actually, regardless of education, liberals are more likely to get wrong facts about the opposition than were conservatives. That is, liberals were more likely to not understand what they disagree with the opposition with. So what it, I think, reflects is that we’re more likely to be living in urban bubbles where we talk to each other. And while we believe that it’s good to be outreaching, we actually don’t do it. So I think it’s actually very important to get out and talk to people, see who they really are, and that’s what I’m hoping my book will help people do, invite people to do.

JW: You say the people in Pikeville who you talked to and became friends with actually feel ignored and left behind, but actually Joe Biden has not ignored Appalachia or the poor parts of the country. His key legislative achievements, the Infrastructure Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, the CHIPS Act, brought tens of billions of dollars to the poorer, Trumpier parts of the country. And you say that even in Pike County, there’s been positive economic news for the last few years. Do people in Pikeville have any sense of what Joe Biden and the Democrats are actually doing to help them?

AH: No. No, they really don’t. One person told me Biden really has a visibility problem and Kamala doesn’t have much time to make up for that. But I was talking with Mitch Landrieu who went around to many Midwest red states asking just this question. “Do they know that actually the Build Back Better Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, these are actually going to help red states more than blue states?” No, they don’t actually know that, and I think we need messengers out there for carrying that message. It’s not out there yet.

JW: One last thing. You are a white woman intellectual, a Berkeley professor, and yet you managed to get working class white men in small-town Kentucky to talk to you. How did you do it? What did you tell them about your project?

AH: We began with that. I came from outer space from their point of view. I couldn’t have a worse place to have come from. But one guy said to me, “Well, there are a lot of stereotypes about hillbillies in Appalachia and it’s terrible. A lot of those stereotypes are negative.” And I said, “I know just what you mean. I come from Berkeley, California and I face the very same thing,” and we both laughed.

JW: In that speech of Bill Clinton’s at the convention urging Democrats not to demean Trump supporters, he added, “But don’t pretend you don’t disagree with them if you do.” Did you tell your people in Pikeville what you think about Trump?

AH: Yes, of course I did. And they knew it from the get go. But they talked to me, I think, because they didn’t want to be misunderstood. But yes, I did, and I am an open book. If you Google my name, and especially my university website, you’ll see all my op-eds and you’ll know exactly where I stand and have for a very long life. But a lot of people there don’t feel like many people from the other side can move beyond their judgment, can turn their alarm system off long enough to get bilingual and understand how they hear so that you can get messages to them before this election. I know that a lot of Trump supporters are going to vote the way they have voted, and so I feel in the days that remain, we need to focus on swing states and undecided voters. I think that is the first thing to do but do it with respect. It doesn’t cost you anything.

For me, the biggest hero is Nelson Mandela. A country was about to have a bloodbath and he didn’t say, ‘I’m just going to judge the other side and consider that that’s going to solve the problem.’ No, he actually spoke Afrikaans and he won, but he won them by a combination of reach-out and he negotiated on the basis of respect. I think we’ve got to do that.

JW: Arlie Hochschild – her indispensable new book is Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right. Arlie, thank you for this book, and thanks for talking with us today.

AH: Thank you so much. Lovely talking with you.